Dying Languages

February 11, 2022

When you think of a dead language, what is the first one that comes to mind? If it’s Latin, you’d be right, but have you ever wondered what killed it in the first place?

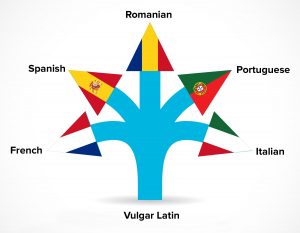

A dead language is one that lacks any native speakers. Today, no one speaks Latin as their first language, but one might argue Latin is still alive. Despite having no native speakers, Latin is still vital to

Catholicism, the root of the Romance languages (Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Romanian,) and is used today for naming animals, body parts, and chemicals.

Catholicism, the root of the Romance languages (Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Romanian,) and is used today for naming animals, body parts, and chemicals.

Even though it is still used for religious and academic purposes, Latin remains six feet under and is likely never to be revived in a conversational manner because of its complexity. There is no need to, since other languages have taken its place in widespread communication. Today, many languages are on the verge of suffering Latin’s fate.

According to an article by The Guardian, The United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) provides a classification system for the statuses of languages. They are as follows:

Vulnerable – Languages only spoken at home

Definitely Endangered – Children do not learn the language at home

Severely Endangered – Grandparents speak it, parents might understand, and children are not taught

Critically Endangered – Youngest speakers are grandparents who speak partially or infrequently

Extinct – No speakers left

Near the top of UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, the Sicilian dialect of Italian claims a vulnerable spot. Though the language has millions of native speakers, the Endangered Language Alliance (ELA) writes that it is in danger of being replaced by Standard Italian. This is because Standard Italian is dominant in use for official reasons and in the media. The ELA reports people are “split upon passing Sicilian on to following generations,” and that “only a third of the population will speak Sicilian at the end of the 21st century.”

Current trends suggest Sicilian and the other 2,500 endangered languages on UNESCO’s list will die out sooner or later. According to National Geographic and a 2008 American documentary, The Linguists, some other dying languages include…

Gottscheerisch (German dialect) – A few thousand speakers

Gottscheerisch originates in the enclave of Gottschee, Slovenia, and was the main language of communication there until 1941. The language developed from German-speaking settlers from distinct regions in southern Austria. In the 19th century, many Gottscheers emigrated to America, and German occupation forces relocated most of them during World War II. After the war, the language took another punch when it was outlawed in Yugoslavia (socialist country established after WWII which included Slovenia). Today, Gottscheerisch only lives on in isolated communities, like a significant one in Queens, New York City, and in the families that remained in Gottschee and preserved the language.

Ainu (indigenous Japanese language) – 2 speakers

Ainu is spoken by a few elderly members of the Ainu people on Hokkaido, the second largest island of Japan. The language, more specifically Hokkaido Ainu, is the last surviving member of the Ainu language family that also included the now-extinct languages of Kuril Ainu and Sakhalin Ainu. Ainu is an isolate because it is not related to any other existing languages. The Japanese government chose to recognize Ainu as an indigenous language in 2008, and as of 2017, is constructing a facility dedicated to preserving the Ainu culture and language.

Chemehuevi (Native American language) – 5 speakers

Chemehuevi is a Colorado River Numic language that belongs to the Numic language branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family. In simple terms, it is related to many indigenous languages across the western United States and Mexico. Chemehuevi was only transcribed by linguists in the early 1900s and studied in the 1970s. The Linguists featured two linguists interviewing and recording one of the last three Chemehuevi speakers.

Hope still remains for dying languages in the form of a nonprofit called Wikitongues. Their mission statement on their website reads: “Wikitongues safeguards language documentation, expands access to mother-tongue resources, and directly supports language revitalization projects.” Despite their imminent demises, dying languages’ cultural significance will never be forgotten and many people are working to preserve them for future generations.